A discussion on Facebook regarding cover illustrations caught my attention. The subject was clothing style depicted in cover art that was not compatible with the timeframe of the novel on which the art was displayed. Most of those who commented found such incompatibility to be disturbing. As a reader, I enjoy fashion details in historical novels. Such details bring the characters to life in my mind’s eye. Fashion, food, furniture, and other matters set the scene so that a reader can place the story in the time. A common point mentioned regarding Jane Austen’s novels addresses the fact that she does not describe her characters’ persons or their clothing in any detail, which is sometimes cause for lament and sometimes cause for curiosity. Why this lack of detail?

Jane Austen did not write historical novels. She wrote of her time for readers in her time. Some details would not have needed a great deal of stress or attention as her contemporaries would have known what she was talking about. However, one still wonders why so little attention was paid to appearances. We know Jane Austen was interested in clothes; her surviving letters to Cassandra frequently discuss clothing in detail. One example of this is the letter from Sloane Street written April 18th-20th, 1811. In this letter, Jane Austen discussed her shopping expedition, in which she purchased muslins for herself and Cassandra, bugle trimming and other items, including a new bonnet, and confessed a desire for a new straw hat.

We also know that Jane Austen had ideas about her characters’ appearances. In another letter from Sloane Street, this time dated May 24th, 1813, she told Cassandra of her and brother Henry’s visit to the Exhibition in Sloane Street, where she saw a portrait of Mrs. Bingley in which “Mrs. Bingley is exactly herself…dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments….” (1) She lamented not finding Mrs. Darcy’s portrait, and speculated that Mrs. Darcy would wear yellow.

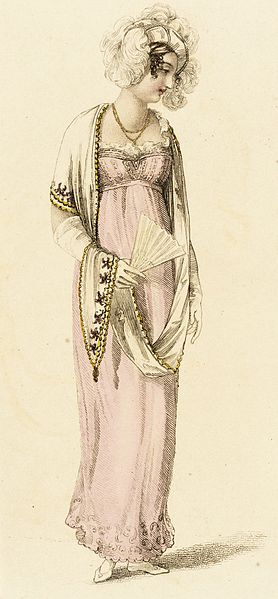

Jane Austen’s earliest novels that were published during her lifetime were written before she was age 30: Elinor and Marianne (which became Sense and Sensibility) was written approximately 1795, when Austen was 20. First Impressions (which became Pride and Prejudice) was written in 1796, and Susan (which became Northanger Abbey) was written in 1798. Some examples of fashion during this time period are:

Portrait of Susannah Wales by her father James Wales, c 1747-1795

Man’s Fashion Plate c 1795

It is important to remember that none of these books were published until much later. In 1801, the family left Stephenton and moved to Bath upon her father’s retirement. After his death in 1805, Jane Austen, her mother and sister moved periodically until finally, in early 1809, her brother Edward made a cottage in Chawton available for the Austen women. Although Jane Austen had revised Elinor and Marianne heavily in 1798, and had sold the copyright for Susan in 1803 (the publisher did not actually produce the novel, and Austen finally bought the copyright back in 1810), none of her books had yet been published. The years between 1801 and 1809 had not been nearly as productive as her earlier years, although she had done some revisions on Susan and started The Watkins (which was never finished). Once settled in Chawton, Jane Austen resumed her work. Revisions on Elinor and Marianne, First Impressions and Susan continued.

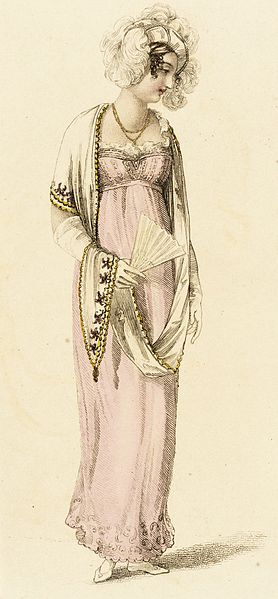

Elinor and Marianne became Sense and Sensibility and was published in 1811. First Impressions became Pride and Prejudice, which was published in 1813. Here are some examples of fashion during this period:

Fashion Plate Half-Dress November 1, 1810

Five Positions of Dancing 1811

Fashion Plate Morning Dress April 1, 1813

As we can plainly see, fashions changed significantly in the period of time between the first drafts and publication dates of Austen’s first two published novels. It is not known if the first drafts of the novels had contained any fashion descriptions. If they did, all such descriptions would have had to be found and revised or removed (not an easy task in the days before computers). If left unchanged, the details would not have added charming historical colour; they would merely have been dated, outmoded, and would have been a distraction to her readers. Jane Austen was also well aware that there was no guarantee of prompt publication once a work was completed. By removing such descriptions (if they had been included in the original drafts) or not writing them in the first place, Jane Austen allowed her readers to visualize her characters for themselves. Certainly, her later novels, Emma, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion, continued this pattern of leaving such details to the imaginations of her readers. I believe Jane Austen deliberately chose not to include such details in her novels. I also believe that this technique contributes to the longevity and freshness of her novels that readers continue to enjoy today.

And that portrait of Mrs. Bingley? There were multiple possibilities, but a favourite contender was a portrait of Mrs. Harriet Quentin by Francois Huet-Villiers, painted before his death in 1813. See an engraving of that portrait produced by William Blake in 1820 here:

Footnote:

(1) JANE AUSTEN’S LETTERS, P. 221

Sources:

JANE AUSTEN’S LETTERS, Deirdre Le Faye, ed. Fourth Edition. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2011.

All images from Wikimedia Commons.